Fracked gas flaring at a fracking well near the Pawnee National Grassland in northeastern Colorado. (Photo: WildEarth Guardians/flickr/cc)

AUSTIN, Texas — Even as Native American activists continue to block construction of the Dakota Access pipeline in North Dakota and the three other states along its planned 1,100 mile trail, U.S. energy pipeline infrastructure — and opposition to it — is expanding elsewhere.

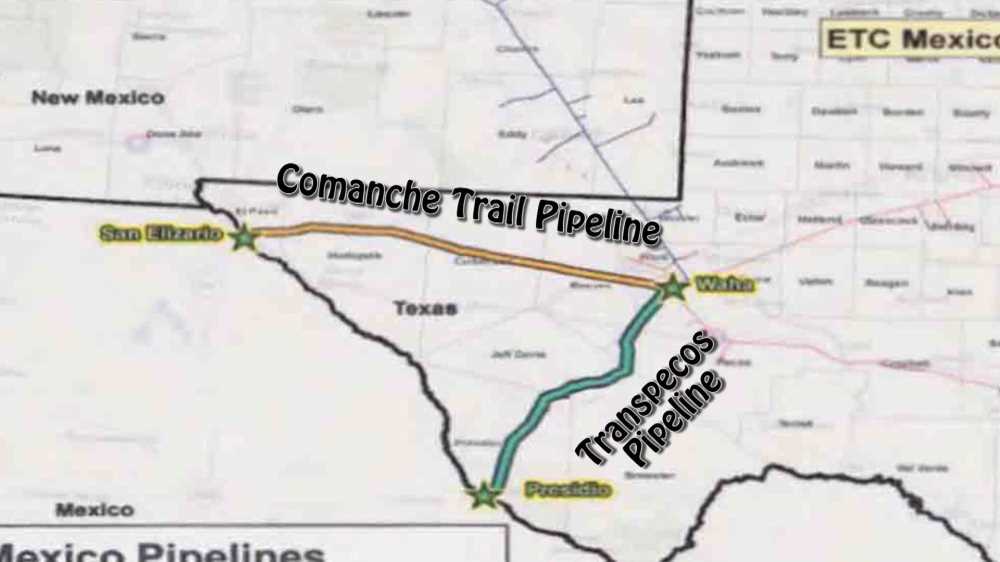

In May, the Obama administration approved two pipeline projects by Energy Transfer Partners, the driving force behind the Dakota Access pipeline. The Trans-Pecos and Comanche Trail pipelines will carry fracked gas from Texas into Mexico, where it will supply the Mexican energy grid.

A map depicting the routes of the Trans-Pecos and Comanche Trail pipelines, which will carry fracked gas from Waha, Texas into Mexico.

“Together, the pipelines will take natural gas obtained from fracking in Texas’ Permian Basin and ship it in different directions across the U.S.-Mexico border, with both starting at the Waha Oil Field,” wrote Steve Horn, a research fellow at DeSmogBlog, on Sept. 20.

Protests have erupted in response to the Trans-Pecos Pipeline in West Texas, particularly in light of Energy Transfer Partners’ use of eminent domain to seize land for pipeline construction from local ranchersand landowners. Activists argue that the legal principle of eminent domain, which is meant to facilitate projects that benefit the public good, should not be used for a construction project that supplies privately-owned energy resources to a foreign nation.

Horn noted that the pipelines are evidence of strengthening ties between the U.S. and Mexican energy markets. He wrote:

“The same month the Obama administration permitted the Comanche Trail and Trans-Pecos Pipelines, the U.S. and Mexican governments announced the signing of an agreement creating the U.S.-Mexico Energy Business Council. This council’s objective is ‘to bring together representatives of the energy industries of the United States and Mexico to discuss issues of mutual interest.’ Its membership list is a who’s who of major oil and gas players.”

Members of the business council include a top Halliburton lobbyist and key advisors to former President George W. Bush.

Pipelines to carrying gas from Texas to Mexico, eventually reaching the city of Guanajuato, are laid underground near General Bravo, in Nuevo Leon state, Mexico.

U.S.-Mexico pipeline construction has also caused conflict within Mexico’s Indigenous communities. On Friday, one person was killed and several others injured in northwest Mexico as members of the Yaqui native community apparently fought over support for a pipeline project, The Associated Press reported. The proposed pipeline, which would bring natural gas from Arizona to the Mexican states of Sonora and Sinaloa, is being built by IEnova, a subsidiary of San Diego-based Sempra Energy.

Meanwhile, Venezuelan and Ecuadorean efforts to control South America’s energy infrastructure have also provoked protest and unrest at times. Writing for CorpWatch in 2008, Jonathan Luna reported that the Wayúu, an Indigenous community of about 500,000 people in northeastern Colombia and northwestern Venezuela, protested a transcontinental pipeline project backed by both nations.

Like so many other Indigenous communities, including the “water protectors” of the Standing Rock Sioux, the Wayúu felt the pipeline threatened their way of life in exchange for few, if any, benefits.

Debora Barros, a Wayúu lawyer, told Luna:

“Our communities feel they have been tricked, made fools of, because these companies came in here buying off and dividing our leaders with minor favors and gifts, and were able to manipulate community support for the project.”

No comments:

Post a Comment